The Vanishing of Joe Pichler: The Day Hollywood Forgot

Joe Pichler Has Been Missing Since 2006

The Day Hollywood Forgot: The Vanishing of Joe Pichler

He was the freckle-faced kid who once stole scenes from a slobbering St. Bernard, the little brother who made James Van Der Beek look taller in Varsity Blues, and the boy who told his mom, “I’m going to be there one day,” while they watched the Oscars together.

Then, on a rainy Thursday morning in January 2006—weeks before his nineteenth birthday—Joseph “Joe” Pichler walked out of his modest Bremerton, Washington apartment and dissolved into the Pacific Northwest fog.

No splash. No scream. No body.

Nineteen years later, the screen is still blank.

The Credits Rolled Too Soon

Bremerton is a navy town forty minutes west of Seattle by ferry, a place where aircraft carriers outnumber celebrities. Joe was born there on Valentine’s Day 1987, the fourth of five children packed into a three-bedroom house on Olympus Drive. His mother, Kathy, waitressed nights; his step-father, Jim, welded submarine parts at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Money was tight, but the living-room carpet became a stage for Joe’s earliest auditions—reciting cereal commercials from memory at age four.

A Bon Marche department-store spot landed him an agent. By six he was flying to L.A. with a backpack full of fruit-roll-ups and a note pinned to his jacket: “Please return to Gate 23 if lost.”

Casting directors saw the gap-toothed grin and almond-shaped eyes and typed him “mischievous but huggable.” He played a young Robert De Niro in 1996’s The Fan, held his own against Wesley Snipes, and cried on cue for Touched by an Angel. When Hollywood needed a fresh face for the Beethoven franchise—after the original Newton family aged out—Joe got the call. Beethoven’s 3rd (2000) and Beethoven’s 4th (2001) went straight to video but sold millions of DVDs; Joe’s paychecks topped $300 K before he was fourteen.

Yet the bigger the credits, the more school he missed. Kathy noticed her son quoting scripts more easily than multiplication tables. In 2002 she yanked him back to Bremerton for eighth grade. Joe sulked for a month, then adapted—joining the chess club, running cross-country, acting in community theatre where tickets cost five dollars and applause came from parents holding camcorders.

He told classmates he’d return to California after graduation, “once the braces are off.” Meanwhile he collected Magic: The Gathering cards—black-lotus, mox-pearl, alpha editions—worth more than most adults’ cars. He kept them in a fire-proof safe under his bed like a dragon hoarding gold.

The Pause Button

High-school wasn’t a red-carpet, but Joe learned to live in both worlds. He worked summers as a caterer on Seattle film sets, once serving salmon to Tom Skerritt while asking about camera angles. Teachers remember a shy senior who wrote an essay on Macbeth entirely in iambic pentameter and still showed up for 7 a.m. weight-room sessions.

In June 2005 he graduated wearing a navy gown and honors cords. His IMDB page sat dormant, yet residual checks arrived quarterly—enough to fund a gap year. Instead of college, Joe took a $12-an-hour job at TeleTech, troubleshooting cellphone bills. He told friends the 9-to-5 felt “honest,” plus it funded the new apartment on Maple Street—second floor, leaky skylight, view of the Olympic Mountains.

That fall he bought a silver 2005 Toyota Corolla with cash. Inside he hung pine-tree air fresheners and a Beethoven bobblehead that nodded with every pothole. He was eighteen, braces off, trust fund unlocked, and plotting a comeback: head-shots updated, online acting workshops bookmarked, Southwest flight to Burbank scheduled for March 2006.

The holidays came. Christmas Eve dinner at the Pichlers’ was loud—guitar Hero duels, cousins in Seahawks jerseys, Kathy’s fudge stacked like Jenga. Joe brought his youngest brother, Matthew, a rare Japanese Pokémon card and promised to teach him “how to talk to girls without sweating.” Nobody mentions darkness; nobody has to.

January 5, 2006 – A Timeline Carved in Ice

Wednesday, Jan. 4 – 6:15 p.m.

Joe leaves work early, telling a co-worker he feels “antsy.” He buys two frozen pizzas and a 12-pack of Henry’s Hard Lemonade. Security cameras at Safeway timestamp the receipt.

Wednesday – 7:30 p.m. to 1:00 a.m.

Card night at friend Toby Daniels’ garage. Players recall Joe winning big—$60 in quarters—then losing it back. He jokes about writing a screenplay titled Poker with Grandma and drinks four, maybe five, bottles. Nobody thinks he’s drunk; Joe paces when he’s tipsy, and he’s pacing.

Thursday – 2:10 a.m.

He drives home, calls his girlfriend in Oregon. She’s half-asleep; they argue about weekend plans. Call duration: 7 minutes.

Thursday – 3:45 a.m.

Lights still on in Apt. 9B. Neighbor hears alternative rock through the wall—Modest Mouse, volume medium.

Thursday – 4:15 a.m. (last verified contact)

Joe dials best friend Sean McCarthy. Sean later tells police Joe sounded “inconsolable,” repeating, “I just want to be a stronger brother… I gotta go… I’ll call you back in an hour.” The line clicks. Sean redials at 5:30; voicemail.

Thursday – daylight

Joe fails to show for his 10 a.m. shift. Manager assumes flu.

Friday, Jan. 6

Still no call. Kathy drives to the apartment—door unlocked, lights blazing, Xbox on pause. Wallet and car keys missing. Bed untouched. The fire-safe is ajar; rare Magic cards gone. She phones Bremerton Police; an officer takes a report but waits forty-eight hours before entering Joe into the national database—standard for adults, devastating for families.

Sunday, Jan. 8 – 6:40 p.m.

A jogger spots the silver Corolla parked under the Warren Avenue Bridge, nose toward the Port Madison Narrows. Inside: cellphone on passenger seat, two pages of handwritten notebook paper, empty lemonade bottles, and the Beethoven bobblehead snapped at the neck.

The Note That Wasn’t a Suicide Note

Detective Robbie Davis reads the pages under floodlights:

“I want to start over…

I want to be a stronger brother…

If anything happens, give my cards to Matt…”

The handwriting slopes downhill. No salutation, no goodbye. Prosecutors call it “cryptic and poetic.” Kathy calls it “a journal ripped out of context.” Matthew insists, “He left saying he wanted to start over—not end it.”

Search-and-rescue dogs scour the bridge at dawn. The water is 42 °F, tidal pull eleven knots. Divers sweep under the pilings; nothing but tires and a shopping cart. A cadaver dog hits on a patch of bramble uphill from the car, but the scent fades.

By Wednesday, the story hits Access Hollywood. Headlines scream “Beethoven Star Missing—Suicide Fears.” The family begs media to wait for facts; comment sections fill with armchair psychology: “Child actors always crash.”

Theories, Tip Lines, and Dead Ends

Theory 1 – Suicide by Water

Lead investigators point to alcohol, despondent phone call, and proximity to deep water. Studies show jumpers rarely surface if tides are strong. Yet Joe’s loved ones counter: he was planning California, bought plane tickets days earlier, and—crucially—left behind the Pokémon binder he’d promised Matthew, something a meticulous collector would never do.

Theory 2 – Accidental Misadventure

Hypothermia can disorient swimmers in minutes. Perhaps Joe wandered under the bridge, slipped, was swept toward the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Again: no shoes, no clothing found; no witnesses to a splash.

Theory 3 – Foul Play / Robbery

The missing Magic cards retail for upward of $15,000. Joe occasionally met buyers through online forums. Could a transaction have turned violent? His apartment lights left on suggest he expected to return.

Theory 4 – Intentional Disappearance

A small faction on Reddit argues Joe staged an exit, craving anonymity after childhood fame. They cite the note’s ambiguity, the wallet’s absence, the fact that his face—aged progressively—could still blend in a crowd. But he left his passport, and Social Security number has never been used.

Over the years, psychics phone in visions of “water, concrete, and the number 7.” A Tacoma waitress swears she served him eggs in 2010; the man paid cash and limped. DNA tests on a skull found near Port Angeles in 2014 took six months to exclude Joe. Each click of the lab technician’s mouse resets the family’s heartbeat.

What the Detectives Missed

Kathy Pichler doesn’t mince words on the Surviving Parents Coalition website: “Evidence was lost. Surveillance video from a nearby gas station was recorded over. My son’s case was handled like a runaway adult.” She lobbied Washington legislature until 2011, when the state reduced the waiting period for filing missing-person bulletins from 24 to 4 hours for 16- to 21-year-olds.

Janet Bates, a Longview volunteer who has worked on 300+ cold cases, keeps Joe’s poster in the windshield of her Honda. “I live and breathe this kid,” she says. “I won’t let him collect dust.” She’s mailed cards to every U.S. embassy from Uruguay to Uzbekistan, certain that if Joe is alive, someone somewhere has seen his right-forearm tattoo: a red Star Wars rebel insignia.

Life Goes On—Except When It Doesn’t

Three nieces and a nephew have been born since 2006; Kathy buys five birthday cakes, one always decorated with a yellow fondant question mark. Matthew became a middle-school teacher; he keeps Joe’s Beethoven call-sheet laminated in his wallet. Every January 5, the family releases nineteen sky lanterns—one for each year Joe lived, one for every year he’s been gone.

The apartment on Maple was painted teal and rented to Navy trainees. Still, tenants report the Xbox sometimes ejects discs at 4:15 a.m. It’s probably wear-and-tear; Kathy prefers to think of it as a cosmic glitch.

Could He Still Be Out There?

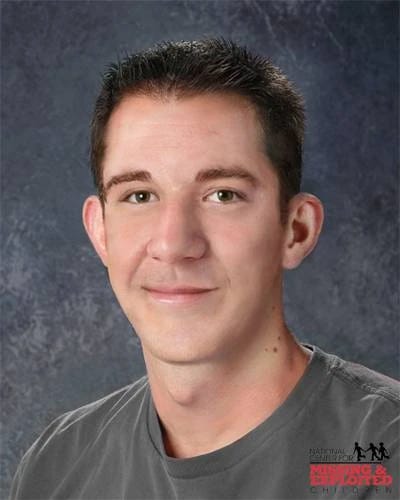

Facial-recognition software has scanned DMV databases in all fifty states; no hits above 70 percent certainty. In 2022, a machine-learning lab aged Joe to 36: receding hairline, same dimple, jaw squarer. The image now appears on milk cartons in 2,700 Walmarts.

If alive, Joe would be thirty-eight. He could be pouring lattes in Portland, coding in Copenhagen, or fishing off Kodiak with a beard that hides the rebel tattoo. He would still love dogs, still quote The Simpsons, still shuffle cards like a Vegas dealer. And he would still owe Sean McCarthy a phone call—one hour overdue for nineteen years.

How You Can Help

Bremerton Police Department case #06-8791 remains open. Tips can be e-mailed to coldcase@ci.bremerton.wa.us or phoned to 360-473-5220. Reference NCMC #1035785 if calling the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Share his age-progressed photo—not the child-star headshot—so grocery clerks, hostel managers, and ride-share drivers see the man, not the memory. Post with hashtag #FindJoePichler; tag @BremertonPD.

If you collect Magic: The Gathering, watch for black-lotus or mox-pearl cards with tiny edge-knicks Joe described as “teeth marks from shuffling.” Each trace matters.

Fade-Out or cliff-hanger?

Hollywood endings hinge on timing: the last-minute phone call, the detective who reopens the box. Real life doesn’t promise closure. Joe Pichler’s story sits mid-scene, camera rolling, audience leaning forward, waiting for someone—maybe you—to yell “Cut!” and finally roll the credits that spell, simply, “Found.”