The Texas Mystery of Raymond Lightner’s Cold Case

Raymond Lightner is a Cold Case That Needs Solved

Raymond Lightner, a Texas Mystery

Raymond Lightner was eighty-one years old on the last day of his life.

He had spent most of those years in Taylor, Texas, a small city framed by cotton fields and the slow arc of the San Gabriel River. Neighbors knew him as the quiet man who walked to the post office each morning, who kept a neat yard on Sixth Street, and who, even after arthritis bent his fingers, still waved from the porch. Few could have imagined that the summer of 1992 would end with his name added to the state’s long list of unsolved homicides, or that three decades later the Texas Department of Public Safety would still be asking the public to help piece together the final hours he spent on earth.

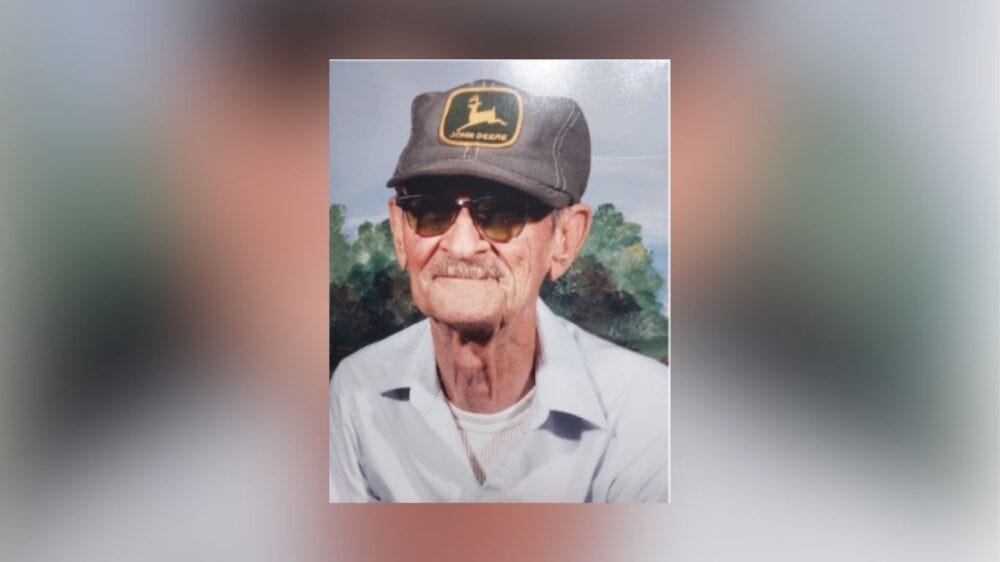

Born in 1911, Lightner had lived through world wars, the Dust Bowl, and the arrival of electricity in rural homes. He worked as a machinist for the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad, retiring in the early 1970s when the roundhouse scaled back operations. After retirement he stayed active, repairing lawn mowers in a backyard shed and trading small favors for home-cooked meals. He never married and had no children, but photographs from the time show a lean man with wire-rimmed glasses who seemed comfortable in solitude. Those same photographs now sit in a case file at the Texas Rangers cold-case office, annotated with dates, addresses, and the circled words “blunt-force trauma.”

July 27, 1992, began like most summer days in Taylor: hot, humid, and loud with cicadas. Lightner rose early, according to later statements from the mail carrier who saw him collect letters shortly after nine o’clock. He was wearing khaki trousers and a short-sleeved plaid shirt, clothes that would later be cataloged by evidence technicians. At some point during the morning he walked three blocks south to a neighborhood grocery, bought a loaf of bread and two cans of soup, and declined the bag boy’s offer to carry the small sack home. That was the last confirmed sighting of him alive.

The first sign that something was wrong came the next morning. A neighbor noticed that the front door of Lightner’s white frame house stood ajar, an unusual lapse for a man known to lock up even when watering plants in the yard. After knocking and receiving no answer, the neighbor contacted police. Officers entered shortly before noon and found Lightner on the living-room floor. Blood spatter marked the faded wallpaper, and the coffee table had been overturned. Investigators determined that he had been struck multiple times with a heavy, possibly metal, object. Nothing obvious appeared to be missing: a wallet still held 47 dollars, and a small television remained unplugged but in place. The absence of clear robbery motive complicated early theories, leading detectives to consider alternative explanations ranging from personal vendetta to random intrusion.

The Taylor Police Department, with only eight full-time officers in 1992, requested assistance from the Texas Rangers and the Department of Public Safety crime laboratory. Over the next two weeks technicians photographed the scene, lifted latent fingerprints, and removed sections of flooring for serology testing. They also collected a half-eaten sandwich from the kitchen counter and a metal flashlight found beneath the couch, items that might have held trace evidence. Autopsy results released in August confirmed that death had been caused by repeated blows to the head and torso, delivered with enough force to fracture ribs and the left zygomatic bone. The medical examiner fixed the time of death between 7:30 p.m. and 10:00 p.m. on July 27, narrowing the window in which witnesses might have seen visitors or heard disturbances.

Detectives canvassed Sixth Street and adjoining avenues, interviewing more than seventy residents. Several recalled hearing what they described as “banging” sounds around nine o’clock, but dismissed them as backfiring cars or fireworks common before the annual Williamson County fair. One teenager thought he saw an unfamiliar pickup truck parked two houses away, describing it as light-colored, possibly blue, with a primer spot on the passenger door. The composite sketch of the driver—white male, mid-thirties, wearing a baseball cap—was circulated in the Taylor Press and on bulletin boards at local churches, yet it generated no actionable leads.

Investigators also examined Lightner’s personal papers, hoping to uncover debts, disputes, or distant relatives who might benefit from his death. Bank records revealed a modest savings account, never more than a few thousand dollars, and no safety-deposit box. A canceled check showed he had recently paid for a new roof, work completed by a crew from out of town. Detectives tracked down each laborer, verified alibis, and ruled them out. Similarly, a review of the machinists’ union local turned up no grievances tied to Lightner’s thirty-year employment. The portrait that emerged was of an elderly man who lived simply, avoided conflict, and had, by most accounts, few enemies and even fewer close friends.

By the end of 1992 the investigation slowed. Tips called into a dedicated hotline tapered from several each week to a handful per month. Physical evidence collected at the scene was cataloged and placed in storage, awaiting scientific advances that might provide clearer answers. In 1994 a newly assigned detective ordered mitochondrial DNA testing on scrapings from beneath the victim’s fingernails, but results were inconclusive, contaminated perhaps by decades of handling at the rail yard where Lightner had spent his career. A second attempt in 1999, using improved PCR techniques, yielded only partial profiles insufficient for comparison.

The case file changed hands multiple times as veteran investigators retired and younger Rangers rotated through the district. Each new detective reviewed the binders, re-interviewed surviving witnesses, and checked emerging databases for similar crimes. No pattern surfaced. Taylor itself changed: the grocery Lightner visited became a thrift store, the rail yard closed, and new subdivisions pushed past the old city limits. Yet the white frame house on Sixth Street remained, repainted and occupied by new families who knew nothing of the violence that had unfolded there years earlier.

In 2019 the Texas Department of Public Safety launched a statewide initiative to highlight cold cases through social media, press releases, and digital billboards. Raymond Lightner’s photograph—taken at a niece’s wedding in 1988—appeared on highway signs along U.S. 79 with the caption “Who killed me?” The appeal generated fresh tips, including one from a woman who recalled her grandfather mentioning a coworker who bragged about “hurting an old man in Taylor.” Rangers followed up, located the coworker’s grandson in another state, and administered a voluntary interview. The story proved false, a confused memory tangled with jailhouse rumors, but the exercise demonstrated that public attention could still reach potential witnesses.

Forensic genealogy, credited with solving high-profile cases across the country, has also been applied. In 2021 a private laboratory uploaded the partial DNA profile to public genealogy databases, searching for distant relatives who might point toward an unidentified suspect. The search produced several third-cousin matches, yet the family trees traced back to multiple states, requiring painstaking archival research to narrow branches. That work continues, sustained by grant money allocated to the Rangers’ cold-case unit and by volunteer genealogists who donate hours combing census records and newspaper archives.

Community interest has not waned entirely. Each July, around the anniversary, local historians place a small notice in the Taylor Press reminding residents that the murder remains open. A neighborhood association planted a crepe myrtle in the park across from Lightner’s old house, unofficially dedicating it to the memory of an man whose life ended violently and anonymously. Schoolteachers sometimes assign the case as an exercise in civic responsibility, urging students to consider how silence—whether from fear, indifference, or faded memory—can allow crime to persist.

Investigators emphasize that even seemingly trivial information could shift the trajectory of the inquiry. Someone may remember an estranged relative who vanished from the area in late 1992, or possess an old photograph that includes an unfamiliar face in the background. A discarded tool, perhaps mentioned in a garage-sale conversation, might match the dimensions of the weapon inferred from medical reports. Advances in forensic technology mean that evidence once dismissed as inconclusive can be re-examined with methods unavailable thirty years ago.

The Texas Department of Public Safety continues to accept tips through its website, by phone, or by mail. Tipsters may remain anonymous, and state law allows certain cold-case information to be sealed from public disclosure if release would compromise the investigation. Rangers stress that the passage of time can sometimes encourage witnesses to come forward, especially as relationships change, loyalties erode, and the burden of secrecy grows heavier with age.

Raymond Lightner’s death left more questions than answers, but it also left a legacy measured in persistence: investigators who refuse to close the file, scientists who re-test evidence whenever new techniques emerge, and neighbors who refuse to let a quiet man’s final moments be forgotten. Whether the breakthrough arrives through a phone call, a DNA match, or an unexpected confession, the goal remains the same—to give an eighty-one-year-old machinist, who once walked Taylor’s streets in the early morning light, the justice that has eluded him since the summer of 1992.