How Helle Crafts’ Husband Tried to Dispose of Her Body Piece by Piece in a Wood Chipper

The Wood Chipper Murder: How Helle Crafts’ Husband Tried to Dispose of Her Body Piece by Piece

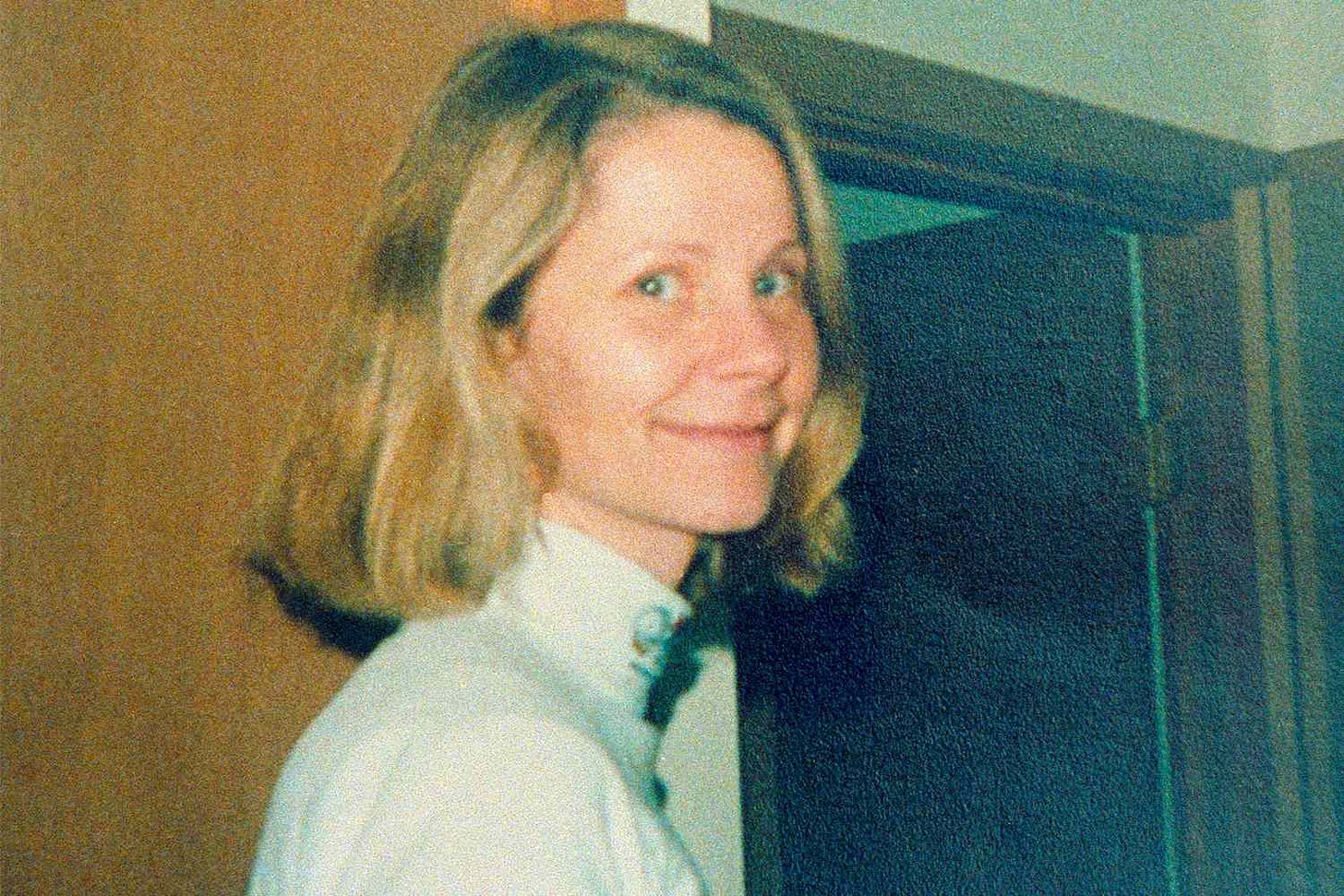

In the quiet town of Newtown, Connecticut, a horrific crime unfolded in November 1986 that would earn the grim nickname “The Wood Chipper Murder” and test the boundaries of forensic science in American courtrooms. The victim was Helle Crafts, a 39-year-old Pan Am flight attendant and mother of three young children, whose disappearance would lead to one of the most shocking murder investigations in Connecticut history.

A Flight Attendant Vanishes

Helle Crafts had built a life that spanned continents. Born in Denmark, she had found her calling as an international flight attendant with Pan American World Airways, traveling the world while raising her family in the affluent Connecticut community of Newtown. On November 18, 1986, she returned home from an overseas trip to Frankfurt, Germany—unaware it would be her final journey.

When Helle failed to report for work days later, concern mounted among her colleagues and friends. Her husband, Richard B. Crafts, offered what seemed at first to be a reasonable explanation: she had gone to visit a friend in the Canary Islands. But this story would quickly unravel as investigators began peeling back the layers of a marriage that had been quietly deteriorating.

The Investigation Begins

What made this case particularly challenging for investigators was the complete absence of a body—a crucial element in most murder prosecutions. Yet as detectives dug deeper into Richard Crafts’ activities in the days following his wife’s disappearance, disturbing patterns emerged.

Richard, a former airline pilot and part-time police officer, had recently purchased a wood chipper—a detail that would prove pivotal to the investigation. Witnesses came forward with chilling accounts: they had seen a man operating a wood chipper on a bridge between Newtown and Southbury in the days after Helle vanished, working in the darkness near the banks of the Housatonic River.

The Gruesome Discovery

Police scoured the area where witnesses had reported seeing the wood chipper. What they found was both minimal and monumental: tiny human remains scattered along the riverbank. The forensic team recovered bone fragments, small pieces of human tissue, and even a fingernail—trace evidence that would become the foundation of an unprecedented murder case.

These microscopic remains told a horrific story. Prosecutors would later argue that Richard Crafts had killed his wife inside their Newtown home on November 18 or 19, 1986, then methodically dismembered her body with a chainsaw before feeding the remains through the wood chipper in a calculated attempt to destroy all evidence of his crime.

A Legal Milestone

The case presented extraordinary challenges for the prosecution. Connecticut had never before secured a murder conviction without a complete body as evidence. The forensic team had to prove not only that a murder had occurred but that the scattered remains belonged to Helle Crafts and that her death was a criminal act rather than an accident or natural causes.

The evidence was painstakingly assembled: forensic anthropologists analyzed the bone fragments, forensic pathologists examined the tissue samples, and investigators pieced together the timeline of Richard’s activities. The wood chipper itself became a crucial piece of evidence, with experts testifying about how such a machine could be used to dispose of human remains.

Trial and Conviction

Richard B. Crafts was arrested in 1987, but the path to justice would not be straightforward. His first trial ended in a mistrial when one juror refused to continue deliberations—a setback that only delayed the inevitable. At his second trial, the prosecution presented a compelling case built on forensic evidence, witness testimony, and Richard’s own suspicious behavior.

In November 1988, a jury found Richard Crafts guilty of murder, marking the first time in Connecticut history that a murder conviction was secured without a complete body as evidence. The verdict was a landmark moment in American jurisprudence, demonstrating that modern forensic science could overcome the traditional requirement of corpus delicti—the body of the crime.

A Judge’s Sentence and Family’s Anguish

At sentencing, the court heard from Richard’s own family members, who urged Judge Martin L. Nigro to impose the maximum penalty. Karen Rodgers, Richard’s sister who had taken custody of the couple’s three children, spoke directly to the court about her brother’s apparent lack of remorse.

“I am concerned that Mr. Crafts has not publicly nor privately demonstrated any remorse for the murder of his wife,” Rodgers told the court. “I believe he has paid lip service only to the concerns of his children.”

Richard himself addressed the court, acknowledging the perception of his emotional coldness while maintaining his innocence. “A great deal has been said about my apparent lack of emotion: ‘He has ice water in his veins,’” he said. “I have feelings like everyone else.” But these words rang hollow in a courtroom where no tears were shed for the victim and no responsibility was accepted.

Judge Nigro ultimately sentenced Richard to 50 years in prison, rejecting defense motions to overturn the conviction or grant a new trial. The sentence reflected both the brutality of the crime and the calculated nature of the cover-up attempt.

The Aftermath and Legacy

Richard Crafts maintained his innocence throughout his incarceration, but the evidence against him remained overwhelming. Decades later, the case resurfaced when he was released earlier than many expected under a now-defunct “good time” credit law that applied to inmates sentenced before 1994. His release reignited debates about sentencing laws and whether justice had truly been served in such a horrific case.

The “Wood Chipper Murder” left an indelible mark on American criminal justice. It demonstrated that forensic science could solve even the most cleverly concealed crimes and that murderers could be convicted even without traditional evidence like a complete body. The case became a touchstone for forensic pathologists and criminal investigators, showing how microscopic evidence could be woven into a compelling narrative of guilt.

For Helle Crafts’ three children, the case represents both loss and legacy—growing up without their mother while knowing that justice was ultimately served through the dedication of investigators who refused to let her disappearance remain a mystery. Her story serves as a reminder that even the most calculated attempts to conceal a crime can be overcome through persistent investigation and advancing forensic science.

The bridge over the Housatonic River where witnesses saw a man operating a wood chipper in the darkness of November 1986 remains a haunting landmark in Connecticut criminal history—a place where one man’s attempt to literally dispose of his wife piece by piece became the evidence that would ultimately convict him of murder.